|

by Dr. Jeffrey Lant

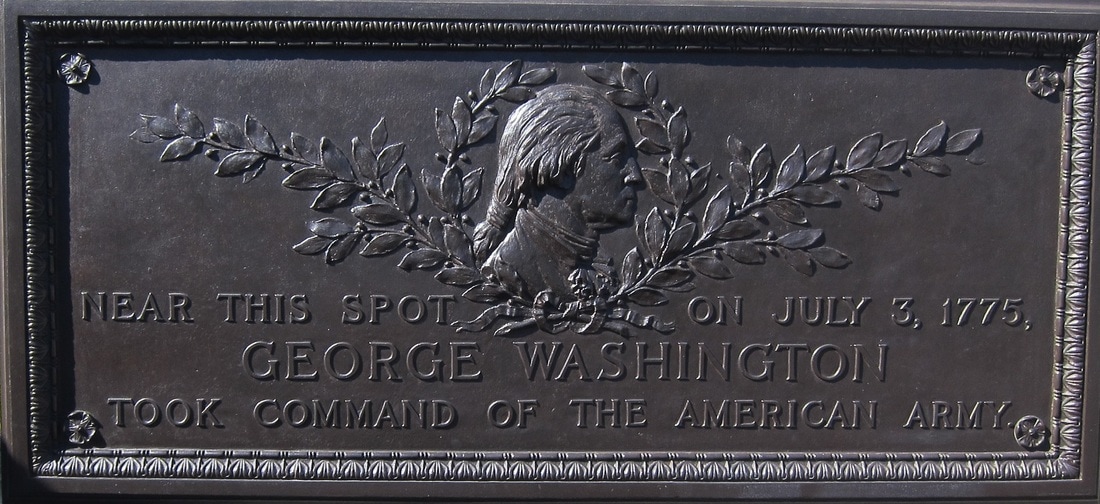

Author’s program note. Today is the first day of spring. I open the shutters, strictly closed against the dreary winter just passed. It is vibrant… it is radiant… it is the sun as we have not seen it for some months now. Of course, being that we are in New England, we must take nothing for granted. The calendar says spring, but I reckon winter has at least one great blast left for us. Heavy wet snow in the morning, melted by afternoon. Spring is to me a reminder, personally delivered, saying summer visitors are just around the corner. Prepare. If you’re not organized, they’ll come anyway, but you’ll be forced to tell each of them the facts that follow. This is time consuming, and results in visitors being given different “tours”… some long and leisurely, others rushed, because I have other things to do. This year I intend to approach the matter differently. And so I am writing for you, dear traveler, the facts I feel that you must have and know about this place you are visiting. For this is no ordinary place, as you will soon see, and it would be most unfortunate if you came and went without knowing why it is so distinctive and significant. How history should be told I have been a writer on historical subjects for over 50 years. I am now clear on what it takes to write history that people will read and understand. For the goal of history is never to exult the writer, but to inform the reader. The worst possible way of doing this is to rely on dates to carry the story. Pilgrims came here on such and such a date. Abraham Lincoln visited on such and such a date. George and Martha Washington were resident here from such and such a date to such and such a date. This is not history; this is a historical obstacle course. It may work for crossword puzzles, but it does not do if you want to know and retain something of significance about this or any other place. Dates are significant only to provide clarity on just when certain things happened. But if you say nothing but dates, you must perforce bore your audience. It is hardly any wonder why so many youngsters in our school systems rate history at the bottom of their favorite classes and groan about the dates they were forced to memorize. But history is not a matter of dates alone, it is a matter of people… what they did, when they did it, how they did it, why they did it. And so history becomes the greatest subject of all, for it is about all of us, each in our turn, each in our way, each in our time. So now I want you to join me on the north side of the Cambridge Common. It is where I have lived for the last 40 years or so. This does not necessarily mean that I know anything about the place, for the mere passing of time or close proximity does not confer insight or a credible understanding of what is all around me on any given day. It is my intention that when you put down this article and come and visit, you will be prepared for the great stories that took place just steps away, and which shaped a nation and the lives of millions. We begin. God The Pilgrims landed in North America in 1620. Most were sick. All were debilitated. Many died. No one emerged unscathed. These people came through the terrible North Atlantic in pursuit of the God who governed and directed them. They landed at Plymouth Rock, and were so bereft of provisions that when they found a few Indian graves near the beach, they ransacked these tombs for corn and other foodstuffs and devoured the contents. The colony hung by a thread through the long terrible winter of 1621. The spirit may have been willing, but the bodies, frail and pathetic, were weak. It took them a full decade to arrive at what was then called Newtowne. Sir Richard Saltonstall, from a prominent English family, landed his party at a bend in the Charles River. And to show you how little time has elapsed from that event, I used to banter with Senator William Saltonstall, a direct descendant, in summers at Manchester-by-the-Sea. We must not, therefore, think of the Pilgrims as far distant, but as much closer to us than we usually allow. The Pilgrims were motivated by two great objectives. One, and always prime, was their direct relationship with God. They also wanted to know what was “out there”. To understand these early days and what has come since, we must do the conjuring trick of erasing from our minds any idea, anything we consider modern, and put ourselves precisely in the shoes of the Pilgrims, whose survival on this continent was not guaranteed, and for whom longevity seemed an elusive possibility. Nonetheless, they regularly sent out scouting parties to see what they could see of the natives, who they knew were there, and of the many things they knew nothing about at all. Thus what takes the modern traveler just about 53 minutes by car, from Plymouth to Cambridge, took ten years… with no path, no guide, not even wayward hearsay and gossip to enlighten them. We must never forget how far they went when going anywhere at all was a matter of faith and determination. In due course, they arrived at Newtowne, a place of swamps and disease. Their needs were basic and immediate… which leads to the first macabre tale. On the south side of the Common, just up a bit from what much later became Harvard Square, you will find a cemetery… unkempt… a place for vagrants… an outdoor urinal. Thus showing there is no respect for the dead. This, curiously enough, was a Puritan belief as well. The first cemetery that was placed on that sight offered no reverence for the dead. Pilgrims who died were thrown over the parapet to be eaten by beasts. There is no demarcation left of just where this way of burial was handled. The marks have been lost over time. It often puzzled me why the bodies were treated with such scant respect… but then I began to think of all these Pilgrims had to do to keep body and soul together under the most unhappy circumstances. There was simply too much to do, and too few to do it to worry about whether the mourning niceties had been kept. Thus once the spirit left the body, the body was thrust away, a thing of no significance whatsoever, and treated accordingly. Created in 1630 The Cambridge Common was created in 1630. It was a place for the members of the congregation to pasture their cows and other livestock. The enclosure movement, which rocked English society in the 18th Century, was not yet common in North America. The communal land that constitutes the Common was therefore at the heart of their way of living. It was not that they necessarily liked each other, it was that they needed each other. And perhaps the worst thing that can happen to a people is they no longer need each other, and so become careless about their relations, thus leading to terrible social consequences. On the Common, just 8.5 acres in size, more was going on than just tethering animals on common ground. When you stand in the middle of the Common as I have done so many times over 40 years, you must be aware of the great events that occurred all around you. First, in the 17th Century, the sheer arrival of these people and their inspiring trek to religious freedom for all constituted an event of epic importance. This was the first place in the world where genuine freedom of belief came to exist. Of course, it didn’t happen without incident or tragedy. No great event involving religion has ever taken place without brutality and intolerance. It seems that every culture says, in its own way, “I love me, so I have no regard for thee.” The true message of New England and of the Common is that here, people finally came to grips with the necessity for tolerance and diversity… which ultimately became the 1st Amendment of the U.S. Constitution. Look around you now… if you are a believer, you are welcome here to believe. If you are a non believer, you are welcome here to believe nothing more than you care to. These are grand ideas, by no means inevitable. Unfortunately, of course, not everyone agreed. And so, on the perimeter along what is now Massachusetts Avenue, there is a plaque, so often covered with weeds, commemorating the migration in 1636 of the Reverend Thomas Hooker from his intolerable situation. It is worth noting that not only was religious diversity advanced here, but the rights of women too. Anne Hutchinson (1591-1643) was not only a significant theologian, but she was a woman doing the theological work of men, suffering accordingly. This is why, when you look upon the Common, you must see first intolerance, then slowly diversity. Cambridge showed the way and still does. Education, the next great event. The first thing the Puritans had to do was secure hearth and home. This took some time, but as soon as they had done so, they created an educational system not just for themselves, but for, in due course, the general public. Here, the significant name to keep in mind is John Bridge (1578-1665), Puritan. John Bridge had a goal, and that goal was to see an educated people… people who could help themselves solve problems and run a democracy where each man had a vote… an idea which had lay dormant in ancient Greece for 2,000 years. He believed that there could be no salvation without understanding, and there could be no understanding without education. Bridge was obviously a very talented, even charismatic leader, though little in fact is known about him. He arrived in Cambridge in 1632, where he became the supervisor of the first public school established in Cambridge (1635). He served as deacon of the church from 1636 to 1658, and represented the people in the Great and General Court from 1637 to 1641. As a result of his leadership, Cambridge quickly became the most intelligent and well educated town in North America… a designation it has never lost in over 350 years. To commemorate his groundbreaking work, which became a pattern for the new nation, and for every other nation, a large and imposing monument was erected on the Cambridge Common on September 20, 1882. It was given by Samuel James Bridge, of the sixth generation from John Bridge. It stands there to this day… certain, arresting, confident. Here is a man who dared to dream the great dreams, and his great dream was to uplift the downtrodden, the needy, persecuted, and disdained. The public school you went to, wherever it was located, owes a debt to John Bridge and his work in Cambridge. N.B. John Bridge’s descendants kept up their work in providing impacting and instructional monuments. Each was the embodiment of a great idea. Thus, when Harvard College decided in 1884 to depict its founder, John Harvard, there were no likenesses to be had, for there are no known pictures or other representations of the founder. As a result, Sherman Hoar (1860-1898), a member of the class of 1882, was selected as the model for the seated figure known worldwide, a symbol of youth, determination, and idealism. The Bridge family financed this great work by Daniel Chester French (1850-1931), the famous sculptor who designed the Lincoln Memorial in Washington D.C. Lines of people queue for the privilege of rubbing his boot for luck. Revolution In 1775, Cambridge had a population of about 1,500. It was a town where education was valued and God was revered. It was also a town swept by the hot winds of freedom, liberty, justice, and equality… every one a key concept of the late 18th Century intelligentsia. Later, the famous English poet William Wordsworth (1770-1850) said of the French Revolution “Bliss was it in that dawn to be alive, but to be young was very heaven!” That sentiment, if not Wordsworth’s exact words, defined Cambridge in the years of Revolution. Revolutions, after all, are made by the youth who believe the resplendent sentiments which enthrall, captivate, and bewitch them, so motivated no discomfort matters.. nothing matters… but the great thoughts which are the very gospel to them, and which justify anything. This was Cambridge, on the threshold of revolution. Look before you, and consider the situation as the participants must have done. This great idea came alive on the Common. On these grounds, now more accustomed to frisbees and soccer balls, General George Washington took plow boys and transformed them into soldiers, and ultimately these soldiers into victory. Washington moved daily from his grand home on Brattle Street, confiscated from the town’s leading merchant Henry Vassal, who remained loyal to the Crown. Washington on a pleasant day like this would walk to his office in what is now Harvard Yard, just a few blocks away. He was a great man. He was a man who might have been king. Nonetheless he stopped along the way, to check on the well being of his troops. This is what good leaders do. When you see the Common, you must imagine it as it was in its various stages. Troops during the Revolution slept under hastily erected tents, which might mean bringing the materials from home, since the commissary of the newly formed United States was meager, and there was no money for amenities. Men grew hardened under such circumstances or they died; there was no middle ground. What you must consider when you look about the Common is how they lived their lives. Many of them died through disease. The biggest problem of course was what to do with all the human waste, and that of the horses. It was noisome… it was dangerous. And the camp on the Common teetered on the brink of demise from disease. The great figures of the Revolution were not nearly as important just then as the people who discarded the waste and kept disease at bay. But the great figures came nonetheless. In due course they included the household names of the Revolution: the Marquis de Lafayette (1757-1834), Washington’s pet, who returned to Cambridge as part of his great American tour of 1825… General Tadeusz Kościuszko (1746-1817), who came to America with liberty on his lips... and General Henry Knox (1750-1806), whose men brought more than 60 tons of cannons and other armaments from Ticonderoga to Cambridge, approximately 200 miles, step by aching step… an achievement of genius. We should remember, too, Martha Washington. She was in 1775 age 44, a lady of great charm and resources, who brought jellies and other dainties from Mt. Vernon... her kit packed with smiles and cool hands. Last words I hope now through these brief words you understand why I regard these handful of acres as among the very most important and significant in our entire history. Personally, I feel blessed at the thought that I am able to advance and maintain the work necessary to keep the true meaning of this worthy place vibrant and alive, forever. It is a thrill and it is necessary, for without people who remember history, there will be no history to remember. Musical note I have selected to accompany this article the “Old 100th” hymn. Composed in 1551 by Loys Bourgeois, it is arguably the most well known hymn in the Christian repertoire. It is very probably the first hymn rendered by the Pilgrims upon their arrival, although because there are many versions of the lyrics, we cannot be sure which ones the Pilgrims used. “All people that on earth do dwell, Sing to the Lord with cheerful voice. Him serve with fear, His praise forth tell; Come ye before Him and rejoice.” And so, taking their strength from God’s mercy, they found the wherewithal to confront another day. Click here to listen.

1 Comment

Solanki

3/28/2017 10:10:22 am

Amazing.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorDr. Jeffrey Lant, Harvard educated, started writing for publication at age 5. Since then, he has published over 1,000 articles and 63 books, and counting. Archives

August 2018

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed